When the coffee plant was introduced to Brazil in the 1700s, legend has it via a cunning bit of bio-espionage, it flourished. Francisco de Melo Palheta planted the first coffee tree in the state of Pará in 1727 and coffee then spread south reaching Rio de Janeiro in 1770.

At first, Brazilian coffee was mainly consumed by European colonists locally. However, as demand grew in Europe and the United States, exports started ramping up. This blossoming demand caused 1802 to be a pivotal year for exports, and by 1820 Brazil was producing 30% of the world’s coffee.

Around the mid to late-1800’s, disease devastated the coffee industries of Asia, giving Central and South America the chance it needed to really thrive as a coffee region. By 1820, coffee plantations began to expand in the states of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Minas Gerais, representing 20 percent of world production and, by 1830, coffee became Brazil’s largest exporter.

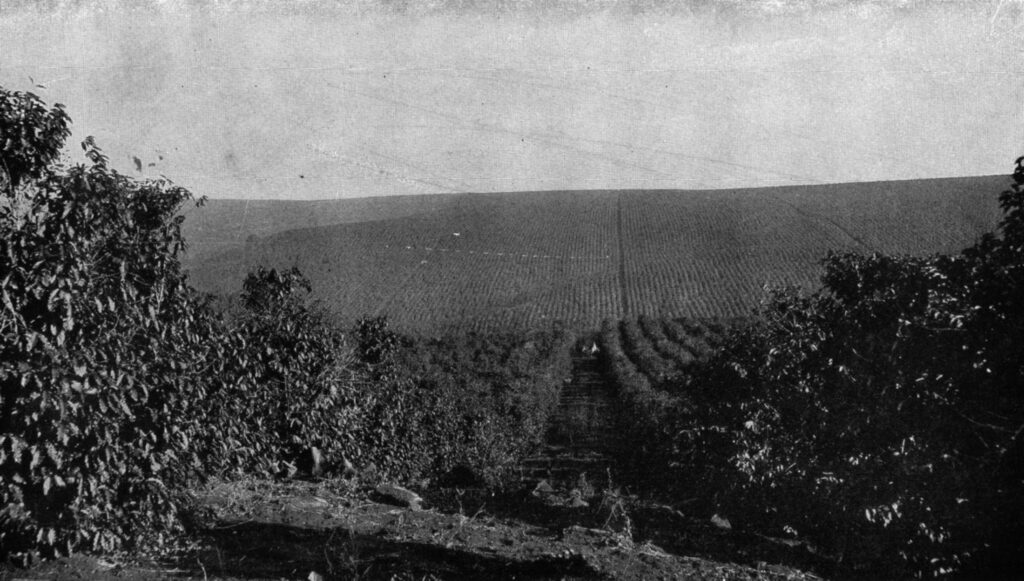

By the early 20th century Brazil had global production in a vice-like grip, supplying 80 percent of all the world’s coffee, and it is still the world’s largest producer with roughly a third of the global supply, or three billion tonnes a year. In total, plantations take up an area almost the size of Belgium, mostly in the cooler, higher altitudes of the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais where the arabica plant is most content.

In the early 90’s, Brazil’s government deregulated a variety of agricultural industries, including coffee. This gave farmers a lot of freedom to experiment, find their own buyers, and sell how they wanted. This also opened up the possibility of buying single origin coffees from the country.

This deregulation opened the gates of innovation, causing Brazil to become a world leader in coffee research and new processing techniques. To this day, Brazil still produces 30% of the world’s coffee supply.

Brazilian Coffee Characteristics

Coffea arabica, the species of coffee plant that grows the highest quality beans, predominates and can be further broken down into varietals. Varietals are hybrids or natural mutations and they keep most of the characteristics of their subspecies but differ from it in at least one significant way.

Typica and Bourbon are the parents of almost all the coffee varietals you’ll hear of. Bourbon is typically more productive and is part of the reason Brazil became one of the world’s coffee super-producers in the 1860s, when it was introduced to make up for the supply loss caused by a leaf-rust outbreak in Java. Slightly sweeter with a sort of caramel quality, Bourbon coffees also have a nice, crisp acidity, but can present different flavours depending on where they’re planted.

There are several uniquely Brazilian varietals. Bourbon itself has coloured varieties including red (Bourbon Vermelho) and yellow (Bourbon Amarelo).

The Mundo Novo varietal accounts for about 40 percent of Brazilian coffees and is a hybrid between Typica and Bourbon that was found in Brazil in the 1940s. It’s particularly suited to the country’s climate and farmers like it because of it’s resistant to disease and high yield. Coffee drinkers like it because it produces a sweet cup with a thick body and low acidity.

The Catuai variety is a cross between highly productive Mundo Novo and compact Caturra, made by the Instituto Agronomico (IAC) of Sao Paulo State in Campinas, Brazil. The plant is highly productive compared to Bourbon, in part because of its small size, which allows plants to be closely spaced; it can be planted at nearly double the density.

The Catucai variety is a cross between catuai and Icatu. Catucai can be both yellow and red and is well-known for its high productivity and yields.

Coffee Processing

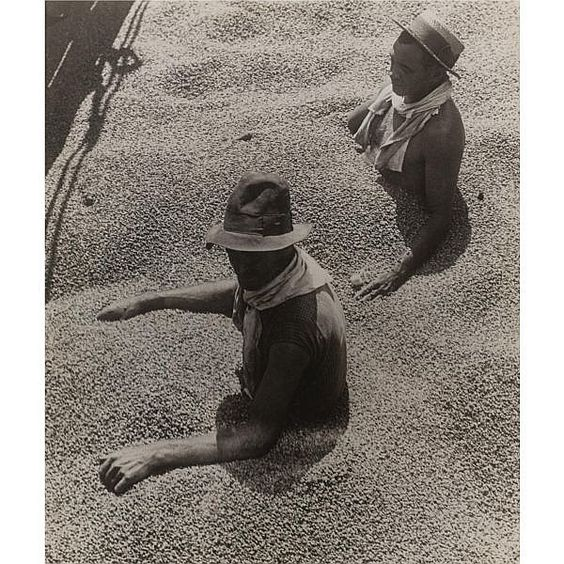

‘Natural’ and ‘pulped natural’ processed coffee are kings in Brazil with naturally processed coffee by far the dominant method of processing. The legend goes that because coffee was traditionally processed this way for 150 years before de-pulping machines were introduced that there is a distinctly “Brazilian” cup. In fact, these processes did help to compensate for the generally lower altitudes in the country and both natural and pulped-natural add a level of sweetness and complexity that would not be attainable without it. In Brazil, the fully washed process is done in very small amounts despite being the dominant processing method across the world.

Some Brazilian beans — especially those that are pulped natural or “Brazil natural” — have a pronounced peanutty quality and heavy body that makes them common components in espresso blends. Chocolate and some spice is typical and the coffees tend to linger in the mouth with a less clean aftertaste than other South American beans.

Specialty Coffee In Brazil

In the 1990s, a movement in Brazil began to establish the country, already the world’s largest coffee producer, as a producer of some of the best coffees in the world. Whereas the ICA quota system had set up state purchasing of coffee, and the subsequent market system did little to reward high-quality production, the Specialty Coffee movement that had started in the U.S. was growing in strength, and quality-focused consumers were now willing to reward growers for their efforts.

The Brazilian Specialty Coffee Association (BSCA) was formed, and the Cup of Excellence, now the world’s foremost coffee quality competition, was organize by the BSCA and others in 1998. Through competitions such as the Cup of Excellence, diverse regions such as Piata, Araponga, Vale da Grama, Piraju, and Carmo de Minas have established themselves as unique micro-climates capable of producing world-class coffees.

Brazilian coffee quality has continued to increase, and over the course of one generation, many Brazilian coffee farms, some known nationally for their coffee quality, have gained international renown for producing some of the world’s best coffees.